Greater Canberra is excited to share the following submission, which was prepared for the 2022-23 ACT Budget consultation.

While Canberra prides itself on being a community where people of all backgrounds can find economic opportunities, our current exclusionary planning system and high rents mean those opportunities are increasingly out of reach for many Canberrans.

This submission focuses on the economic impacts of Canberra’s current high housing costs, and explores the potential for reforms to Canberra’s planning system to reduce rents and house prices. In addition to reducing housing stress for low income Canberrans, our recommendations would expand Canberra’s attractiveness as a destination for Australian workers, and increase Canberra’s long run productivity and economic growth.

1 Key recommendations

-

Reducing housing costs should be a key plank of the ACT’s economic growth strategy.

- Canberra’s high housing costs relative to other Australian cities have reduced the number of people able to afford to live in the ACT, and are making it difficult for Canberra businesses to attract top talent.

- Drawing on analysis of employment, rental, and migration data, we find that for every $1 increase in ACT per week rents above the Australian capital city average, around 18 fewer Australians are able to move to the ACT each year.

-

The ACT’s planning system should be reformed to prioritise increased affordability.

- A range of economic literature shows that removing unnecessary barriers to mid-density homes in urban areas can significantly reduce rents and prices.

- Expanding ‘Mr Fluffy’ rules to all RZ1 land would make dual-occupancy homes easier to build on around 60,000 additional ACT properties.

- Adopting ‘New Zealand style’ zoning reforms in inner urban areas could unlock 30,000 to 50,000 new homes near jobs, transit, and amenities.

-

Reforms to the ACT planning system should be informed by Canberra’s broader economic development goals.

- The ACT Government should directly model housing affordability as part of its ongoing housing supply and land release planning.

- Housing affordability and adequate housing supply should be included as explicit objectives in the next ACT Planning Act.

-

The ACT Government’s Housing Strategy should be revised to increase the Strategy’s ambition with regard to the provision of social housing.

- Consistent with the recommendations of other ACT community organisations including ACTCOSS, the ACT Government should urgently bring forward additional investment in social and affordable housing.

- Any update to the Housing Strategy should review elements of the current ACT planning system that are blocking new social and community housing projects.

2 Impact of high rents on the ACT economy

Housing costs represent a large component of household expenditure across Australia, and are an important contributor to financial stress, in particular among low income households (AIHW, Housing Affordability, 2021).

While much of the media coverage of the housing market focuses on the impact of high house prices, our analysis here largely focuses on the negative impact of high rents. Trends in rents are particularly important to the ACT economy because rates of renting in the ACT tend to be slightly above the national average, and housing costs make up a higher proportion of household expenditure for renters, as compared to homeowners (ABS, Housing Occupancy and Costs, 2019-20).

Our research indicates that recent increases in ACT rents have had a marked impact on the cost of living in Canberra as compared to other Australian capital cities, which has increased financial stress among Canberrans, and significantly reduced ACT interstate migration.

2.1 Trends in ACT rents

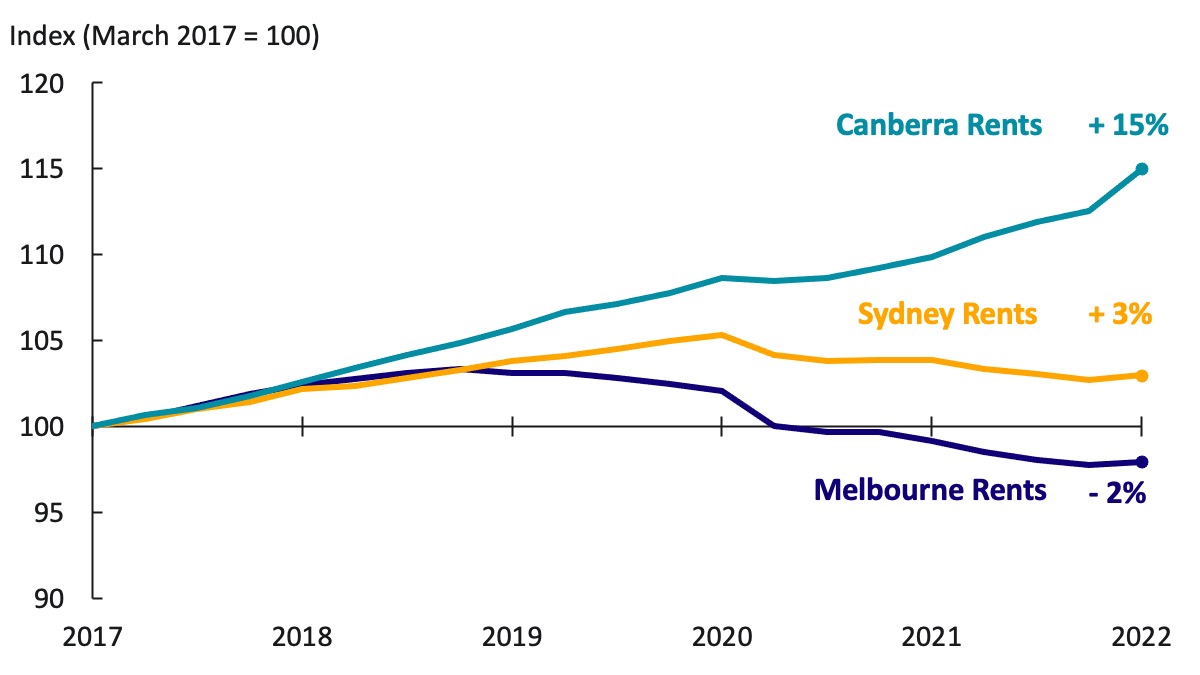

Over the five years to March 2022, Canberra rents increased steadily at an average annual rate of around 2.8%, compared to annual CPI growth of around 2.6% (ABS, Consumer Price Index, March 2022). This has resulted in Canberra rents increasing by a total of 15% over the past five years, compared with an increase of just 3% in Sydney and a decrease of 2% in Melbourne (see Chart 1).

Data: ABS, Consumer Price Index, March 2022.

Data on asking rents - which are often a leading indicator of trends in the broader ABS rents index - suggest an even larger differential between rents in Canberra and other capital cities. CoreLogic data as of the March quarter 2022, indicates ACT median rents were the highest of any capital city at $674 per week, compared with $621 per week in Sydney and $468 per week in Melbourne (CoreLogic, Quarterly Rental Review, 2022). In addition, Canberra asking rents grew at 3.3% in the March quarter, the fastest growth of any capital city.

In summary, these data strongly suggest that the ACT is facing an ongoing shortage of rental accommodation. This is supported by data on residential vacancy rates, which indicates that Canberra’s residential vacancy rates have been persistently lower than 2% since 2015 (SQM Research, Vacancy Rates - Canberra, 2022).

2.2 Impact of high rents on ACT net interstate migration

2.2.1 Historical trends in interstate migration

From April 2013 to December 2014, the annual average quarterly arrivals into Canberra were at the lowest rates they have been since June 2002, varying between 4,500 to 4,800 individuals. From December 2014 to December 2017, this rose steadily to 5,500, before increasing slowly to 5,600 in December 2018. The value fell throughout 2019 and 2020 to 5,000 until rebounding to 5,400 in the March 2021 quarter.

2.2.2 Impact of rents on recent interstate migration

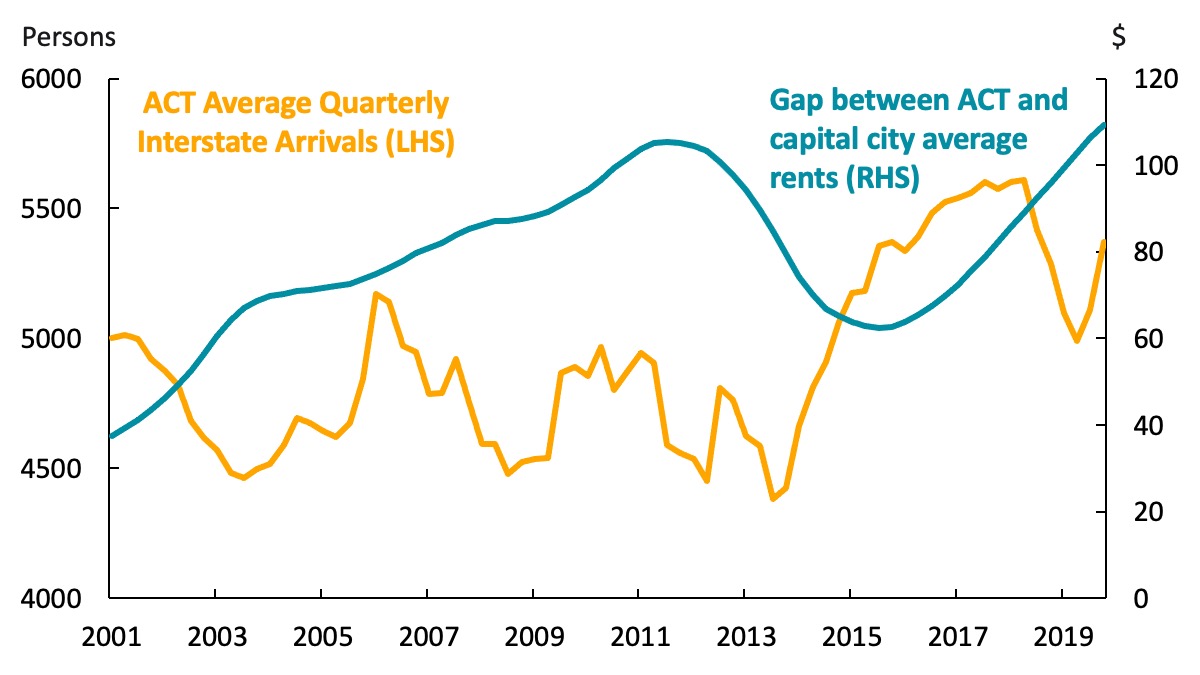

Interstate migration is driven chiefly by employment outcomes and housing costs (NSW Treasury, Intergenerational Report - Chapter 1, 2021). This is evident in data from the ACT over the last 20 years, which shows that interstate arrivals generally decrease as the gap between ACT rents and rents in other Australian capital cities increases (see Chart 2).

Note: Interstate arrivals are a rolling annual average of quarterly data. Historical rental data calculated based on composite of current asking rents and CPI indices. Data: ABS Regional Internal Migration, March 2021. Greater Canberra analysis of ACT Government, Residential Property Market, December 2021 and ABS, Consumer Price Index, March 2022.

Greater Canberra undertook an econometric analysis to better understand the size of the effect of housing costs on interstate migration flows into the ACT. Multilinear regression on data from 2001 to 2020 was used to test the relationship between quarterly arrivals into the ACT and two independent variables: the gap between ACT and Australian unemployment rates, and the gap between average ACT rents and Australian capital city rents.

Overall, we found that a $1 increase in the gap between ACT and Australian capital city rents was associated with a 4.6 person reduction in quarterly arrivals in the ACT, controlling for divergences in labour market outcomes. While the limited sample size for the data means the observed relationship is only weakly statistically significant, this finding is broadly consistent with evidence from other studies.

For instance, Stawarz, Sander, and Sulak (2020) conduct a similar analysis on German internal migration flows and find that a 1% increase in asking rents decreases arrivals by 0.3%. Applying this ratio to recent ACT data would imply that a $1 increase in ACT rents relative to other jurisdictions would lead to 2-3 person decrease in quarterly arrivals. We further note that this analysis may understate the impact of housing costs on the ACT population, as it does not consider the impact of house prices, or the impact of housing costs on interstate departures and international migration.

This analysis illustrates the significant impact that housing costs have had on the ACT’s ability to attract workers and new residents. For instance, our analysis suggests that in the absence of the COVID-19 pandemic, if the gap between ACT and Australian capital city rents had been held constant from March 2018 to the December 2021 quarter, we would expect to have seen an additional 1,200 arrivals into the ACT.

2.2.3 Implications for the ACT economy

This reduction in interstate migration to the ACT has a number of negative consequences for the ACT economy. Principally, this analysis indicates that high housing costs are creating a barrier for employers seeking to bring talent to the ACT, which has negative impacts for both business operating costs and worker productivity.

Additionally, this reduced inflow has consequences for ACT population growth and demographic trends, both because it reduces overall population growth, and because interstate migrants tend to be younger than existing residents (ABS, 2016 Census Update of the Net Interstate Migration Model, 2019).

Lastly, higher housing costs are likely to particularly impact lower-income and marginalised Australians, who are currently likely to be locked out from the considerable employment opportunities and lifestyle benefits available to those who move to the ACT.

2.3 Impact of high rents on ACT incomes

More broadly, the ACT’s current high housing costs have a severely negative impact on financial stress and business competitiveness in the ACT, by increasing the cost of living for Canberra families.

For instance, on current asking rents, an ACT family renting the average detached house will pay a premium of around $13,000 pa compared to a similar Melbourne family (Domain, March 2022 Rental Report, 2022).

Notably, this gap is larger than the $11,476 wage premium in average annual earnings for full-time adults in the ACT as compared with Victoria. In fact, many Canberran families have lower discretionary incomes after housing expenses than households earning substantially less in other parts of Australia, with this burden falling heavily upon the youngest and poorest households (ABS, Average Weekly Earnings, Australia, 2021).

Canberra’s higher rents also affect local businesses by draining money out of the local economy and increasing the wage premium they have to pay to hire workers. Currently, Canberra businesses must remunerate their workers well above the national average just to cover additional housing costs, with these additional labour expenses being passed on to consumers and business customers. Similar issues were explored in analysis from the Global Cities Business Alliance (Housing for Inclusive Cities: the economic impact of high housing costs, 2016), which found that high housing costs have increased the wages that businesses have to pay to attract workers to urban areas. For instance, the wage premium demanded by workers in Sydney was found to be worth $5 billion USD more in 2015 than in a scenario where Sydney rents had risen with inflation since 2010.

As such, high housing costs present one of the largest obstacles to the diversification of the Canberra economy away from the federal public service, as private enterprise in the city faces substantially higher input costs than competitors in other state capitals or internationally.

3 Importance of ACT housing supply

If Canberra wishes to become a more affordable city for low-income Canberrans, and more competitive city for private employers, then we must seek to stabilise and reduce our current high housing costs. As we argue below, this can be done principally by increasing housing supply.

3.1 How housing supply drives housing costs

A wide range of economic literature indicates that reforming planning rules to permit more mid-density or ‘infill’ housing can lead to higher economic growth and sustained reductions in housing costs. To highlight four recent economic papers in this area:

- Hsieh and Moretti (2019) find that planning restrictions that reduce housing supply in urban areas prevent talented workers from moving to jobs that best suit their skills, reducing overall economic output in the United States by a third over a 45 year period.

- Li (2020) analyses the local impacts of new market-rate high-rise apartment buildings in New York, and finds that a 10% increase in housing stock reduces rents by 1% and has a downward impact on property prices within a 500 foot radius. New construction also has a positive impact on local restaurant openings.

- Tulip and Saunders (2019) develop an empirical model of the Australian housing market, and estimate that in aggregate, every 1% increase in the housing supply leads to a 2.5% reduction in housing costs, consistent with a range of international estimates.

- Greenaway-McGrevy and Phillips (2021) analyse reforms to the Auckland planning system that allowed more mid-density developments in inner urban areas, and find that they doubled the rate of new housing construction in the city in the four years after implementation.

Unfortunately, these findings regarding the relationship between planning rules, economic growth, and housing affordability are not reflected in the current ACT planning system. For instance, housing affordability and sufficient housing supply are not explicitly included as objectives of the ACT Government’s draft Planning Bill (see Greater Canberra, Media Release, 2022).

In addition, analysis by Greater Canberra of the ACT Environment, Planning and Sustainable Development Directorate’s housing supply model (obtained through FOI), indicates that current land release and planning decisions are entirely informed by population growth projections, and do not involve direct modelling of infill housing supply. This strongly suggests such planning decisions are being made without adequate modelling of the impacts on housing affordability, or detailed modelling of the potential housing supply impacts of potential new planning reforms.

3.2 Example reform proposal - duplexes on more RZ1-zoned blocks

One simple planning reform that would meaningfully expand the ACT housing supply would be to apply the existing ‘Mr Fluffy’ dual occupancy rules to all RZ1-zoned properties.

Currently, more than 80% of ACT residential land is in the RZ1 suburban zone. Notably, large parts of the Inner North and Inner South are currently zoned RZ1, which severely limits the supply of housing in these high-demand areas located near jobs, public transport, and key amenities (ACT Government, Housing Choices Discussion Paper, 2017).

Existing planning laws strictly limit the ability for property owners to build duplexes (dual-occupancy blocks) on properties in the RZ1 suburban zone in most parts of Canberra. In particular, under current planning laws, duplexes are not permitted on RZ1 blocks with an area of below 800m2. In addition, duplexes on RZ1 blocks are generally not able to be unit-titled, which limits the ability for secondary units to be rented or on-sold.

However, an exception to this rule has already been introduced under Territory Plan Variation 343, which enables unit-titling and development of duplexes on RZ1 blocks larger than 700m2 for ‘Mr Fluffy’ blocks surrendered under the Loose Fill Asbestos Insulation Eradication Scheme Buyback Program (ACT Government, Mr Fluffy blocks, 2022). While detailed data on development under the scheme has not been released, anecdotal evidence indicates that the take-up rate is significant.

Analysis by Greater Canberra indicates that around 20,000 RZ1-zoned blocks in the ACT are currently single occupancies with an area of between 700 and 800m2, while around 44,000 RZ1-zoned blocks are single occupancies with an area of greater than 800m2. As such, simply applying these narrow planning reforms to all RZ1 blocks would represent a substantial increase in the potential supply of new homes.

3.3 Broader reform ideas

Broader reforms to provide more housing options for Canberrans could have an even greater impact on ACT housing costs. For instance, if the inner Canberra suburbs of Deakin, Forrest and Yarralumla were rezoned to accommodate the same population density as the leafy-green Melbourne suburb of Toorak, they could accommodate around 40,000 people in total, up from just 7,400 as at the 2016 census. This would massively expand the supply of homes in the ACT near jobs, transit, and amenities, and have a meaningful impact on housing affordability.

There is similarly strong potential to take inspiration from successful zoning reform efforts conducted overseas. Analysis of planning reforms introduced in New Zealand, which permitted construction of up to three units on all urban blocks, indicates that similar reforms applied just to Canberra’s inner suburbs would allow for the development of 30,000 to 50,000 new homes (see ABC, Media article, 2022).

4 Impacts of high housing costs on economic opportunity in the ACT

Given the negative impacts of high housing costs and inadequate housing supply discussed above, Greater Canberra further echoes the calls from a range of other ACT peak bodies and organisations for additional investment in social housing (ACTCOSS, Media Release, 2022).

In particular we note and support several recommendations made by the ACTCOSS in their recent budget submission including:

- Reviewing the ACT Housing Strategy in light of recent increases in housing costs, with a view to increasing the overall stock of affordable and social housing, and setting a target of zero homelessness.

- Enabling increased development of community housing through release of affordable land, rezoning of existing community-owned land, streamlining of planning processes, and the provision of rates exemptions and discounted valuations where necessary to enable development.

- Resourcing a Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community housing provider, and supporting improved responses to support LGBTIQA+ Canberrans in housing stress.

We note that these recommendations are complementary to ongoing efforts to decrease market rents and house prices. The current high demand for social housing leads to long waitlists, meaning that social housing in the ACT cannot act as a genuine alternative for the many low-income Canberrans facing housing stress in the private rental market. Relatedly, higher housing costs in the private market increase the risk of housing stress and the demand for social housing (see Colburn and Aldern, Homelessness is a Housing Problem, 2022).

By reforming the ACT planning system to provide more affordable market-rate homes across Canberra, and increasing social housing supply, the ACT Government can reduce the number of Canberrans in housing stress while also ensuring adequate social housing units are available for those most at risk of homelessness.

You can download a PDF version of the above submission with additional appendix here.