The Legislative Assembly held an inquiry into the new Planning Bill, as part of the ACT Planning System Review and Reform Project. Greater Canberra made a detailed submission, which you can find below. We also appeared before the Committee hearing for this inquiry, transcripts and recordings are available on the Assembly’s website

You can also download a PDF version of our submission.

About Greater Canberra

Greater Canberra is a community organisation, established in 2021, that is working towards a more liveable, sustainable and affordable Canberra for everyone. We believe that forward-thinking urban planning is vital to ensuring that future Canberrans can enjoy social and economic equality and a high quality of life.

Our members come from all over Canberra, and from a variety of backgrounds - both renters and homeowners, from different stages of life, different levels of wealth, and different occupational and professional backgrounds.

We believe better planning policy can create a more liveable, sustainable and affordable city.

We believe every aspect of the city, from its parks, to its shops, to its public amenities, should make a positive impact on the lives of Canberrans. We value walkability, active and public transport, vibrant and engaging public spaces, and diverse housing that meets the evolving needs of Canberran families.

We believe we can house the next generation of Canberrans through better use of the space we have, not endless sprawl that damages our natural environment. Embracing density will allow more Canberrans to live within the existing urban footprint, in close proximity to workplaces and amenities, allowing a lower-carbon and less car-dependent lifestyle.

We believe that by building more housing of all kinds - both social and market-rate - we can make Canberra affordable for all. For most Canberrans, the ability to afford a home is the difference between economic security and financial stress. Today, many Canberrans struggle to afford a home, unless they already own a property, or are helped by someone who does. This hurts our economy and damages the social fabric of our city. We believe that with the right policies, all Canberrans can afford to live with dignity.

Introduction

Canberra is a growing city with a population growing faster than any other state or territory. This growth brings many benefits, but also a critical challenge: how do we house an increasing number of Canberrans, while simultaneously addressing the housing affordability crisis, fighting climate change and protecting our natural environment?

Canberra deserves an agile and responsive planning system suited for this task. A planning system that supports a growing Canberra, a cheaper Canberra and a greener Canberra.

The Government has undertaken the Planning System Review and Reform Project to modernise the ACT’s planning framework, and deliver a system that is easier to use, enables sustainable growth and provides both clarity and flexibility in outcomes and processes. The Planning Bill sits at the centre of this framework, informing and shaping every element of the system.

We agree with many of the Government’s goals, however we believe that much more needs to be done to achieve them. Over the past year, we have been involved extensively in the consultation processes around the Planning System Review and Reform Project, advocating for a system that promotes a more liveable, sustainable and affordable Canberra. This submission builds on our earlier submission, which is available on our website.

We are pleased to see that the Bill introduced has addressed some of our concerns (in particular, the Territory Priority Projects system), but the Bill leaves much to be addressed. In particular, we highlight two key areas in need of reform

-

Affordability and housing supply must be a core object and principle: Affordability and adequate housing supply need to be at the core of our planning principles - the current Bill does not do this. The objects and principles of good planning are poorly structured and cast affordability as only a peripheral concern.

-

ACAT merits review should be replaced by a more effective and democratic consultation and planning review process: Community input on planning outcomes should occur upstream of new developments. A new ‘exemplar designs’ process should be created to reward community approved building designs of high quality. Merits review, where necessary, should apply equally to all low-impact developments, and be undertaken in a more efficient and effective manner that doesn’t rely on an adversarial tribunal.

We thank the Committee for the opportunity to participate in this inquiry.

Summary of recommendations

| 1 | An ‘equitable and prosperous city’ object should be inserted into the Bill as a coequal object to the ‘ecologically sustainable development’ object. |

| 2 | The ‘activation and liveability principles’ should be split into the separate ‘affordability principles’ and ‘activation and liveability principles’. |

| 3 | Public and social housing should be excluded from third-party ACAT merits review. |

| 4 | ACAT merits review should be replaced with a new, non-adversarial system that is more efficient, accountable and transparent. |

| 5 | District Strategies should include mandatory, ambitious housing supply targets, based on realistic population growth estimates, to ensure that Canberra’s housing needs are met. Extensive community engagement should be used to ensure communities can shape how their district achieves these targets in a fully-informed way, and settle expectations well before individual developments are proposed. |

| 6 | The Government should develop an exemplar designs process that gives streamlined approvals and review exemptions to projects using pre-approved designs. |

| 7 | Third-party merits review should not be available for low-impact projects, in particular smaller-scale multi-unit developments in RZ1. |

| 8 | The Chief Planner should serve at the pleasure of the ACT Executive, without a fixed term. |

| 9 | The principles of good consultation should explicitly acknowledge that public consultation processes should, where possible, include the needs of potential future residents and the broader Canberra community. |

| 10 | The good consultation guidelines should include best practices such as representative population sampling and low-cost forms of engagement (where appropriate, given time and cost constraints) in order to successfully implement the “balanced” and “inclusive” principles. |

| 11 | The activation and liveability principles should be amended to:

|

| 12 | The high quality design principles should be amended to make explicit that local settings and contexts can evolve over time, including through development, to better meet changing community and environmental needs. |

| 13 | The high quality design principles should be amended to include a provision related to building quality and energy efficiency. |

| 14 | The investment facilitation principles should be renamed ‘economic prosperity principles’ to better reflect their nature and aim, and should express a goal of maximising incomes and minimising poverty. |

| 15 | References to “heritage” in the cultural heritage conservation principles should be amended to refer to heritage places and objects that have been registered under the Heritage Act 2004, to provide certainty as to what places and objects engage this principle. |

| 16 | The language of the cultural heritage conservation principles should be reworded to provide that the focus of the principle is to conserve the heritage value of existing heritage places not to constrain nearby development in a way that dampens the potential for architectural expression and the creation of additional housing and services. In particular, references to “proportionality” should be removed to avoid the implication that adjacent developments should be scaled down near to heritage places. |

Housing affordability and reducing poverty must be core principles

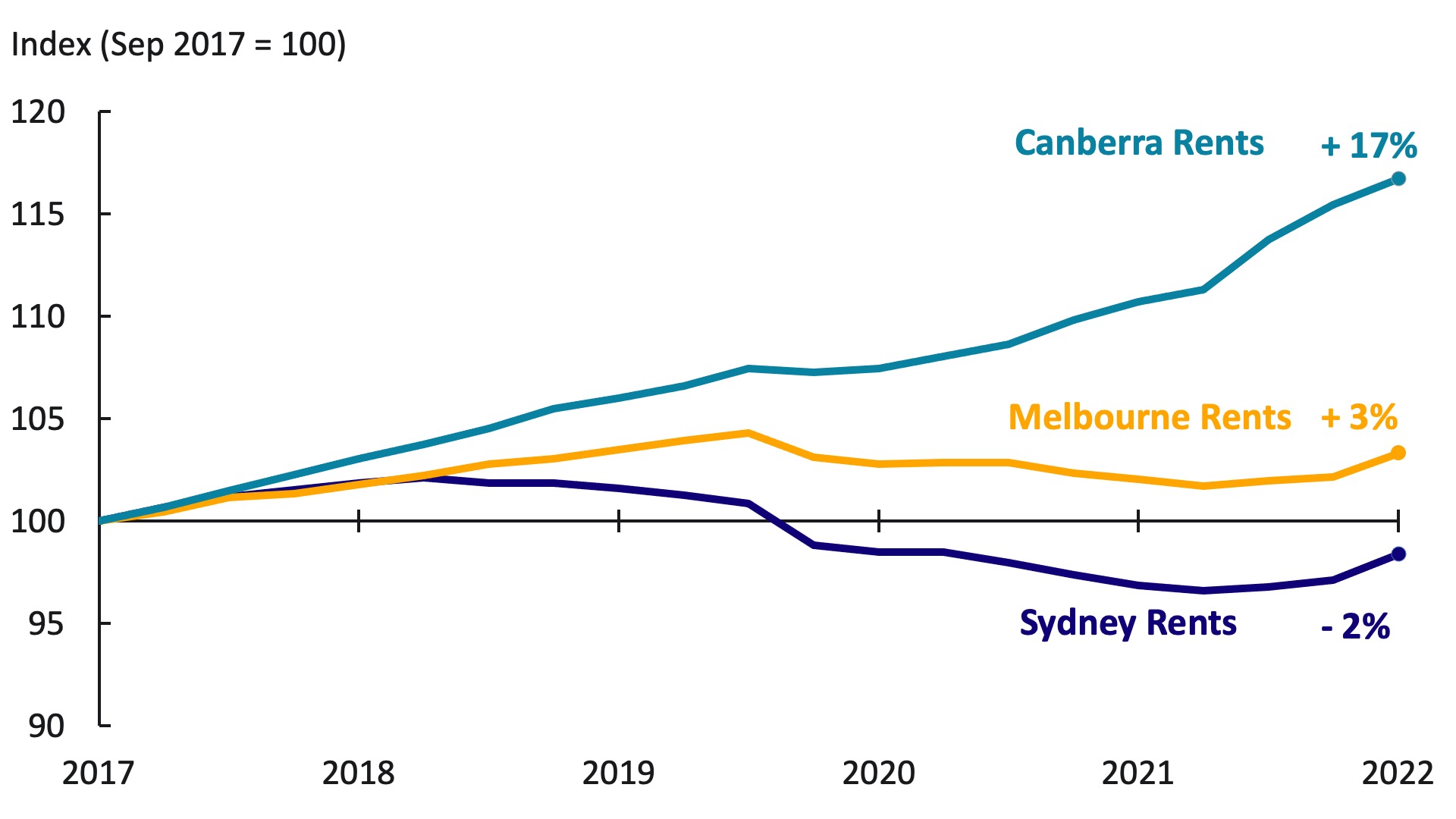

Canberra is among the most expensive cities in Australia in which to rent or buy housing. Figure 1 shows how over the past five years, Canberra rents have risen at a markedly faster rate than rents in Sydney or Melbourne. This is further supported by the recently released 2021 Census data, which indicates that Canberra’s median weekly asking rent is $450 per week, slightly lower than Sydney ($470), but significantly higher than Melbourne ($390) and Brisbane ($380).

Figure 1: Canberra rents compared to Melbourne and Sydney

Data: ABS, Consumer Price Index, September 2022.

It is well established that planning controls have a major impact on housing supply, a key determiner of affordability. It is therefore disappointing to see that housing affordability is not given appropriate emphasis in the Bill’s objects or principles of good planning. The Bill’s outcomes-focussed approach means that the Territory Plan, Planning Strategies and other instruments must be consistent with, promote, or give consideration to the objects and principles of good planning.

It is of paramount importance that the objects and principles of good planning accurately reflect the outcomes that Canberrans expect and need from the planning system. Outcomes omitted from the objects and principles of good planning will be legally and practically excluded from our planning framework.

In our media release after the release of the Bill for consultation, and in our exposure draft submission, we argued that affordability needs to be front and centre in the Bill’s objects and principles.[1] Unfortunately, the current version of the Bill continues to neglect the importance of housing affordability as a core principle.

Case study: The impact of the 2016 Auckland Unitary Plan

Planning reforms can make housing more affordable, as seen in the improvements of housing affordability in Auckland after significant planning reforms in 2016.

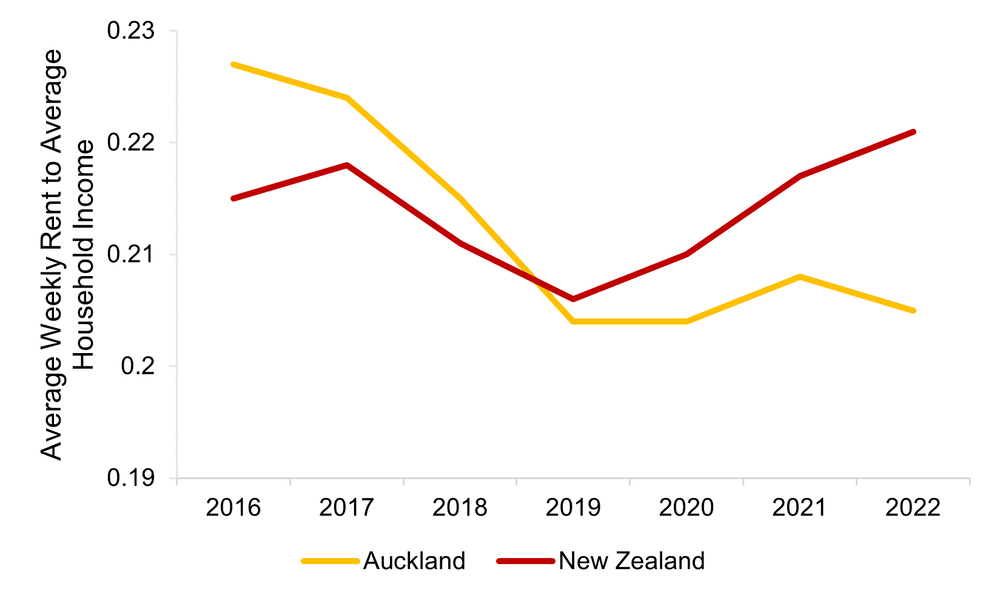

Figure 2: Average weekly rent to average household income in Auckland vs New Zealand, 2016-2022

Graph: Matthew Maltman, One Final Effort, https://onefinaleffort.com/auckland, retrieved 14 Nov 2022, reproduced with permission.

In their paper, Greenaway-McGrevy and Phillips (2021) analyse reforms to the Auckland planning system that allowed more mid-density developments in inner urban areas, and find that they doubled the rate of new housing construction in the city in the four years after implementation. This impact is clear in Figure 2, which shows that the rent-to-income ratio in Auckland fell while the ratio in the rest of New Zealand rose following zoning reform.

Given the substantial impact that planning rules can have on housing affordability, it is clear that affordability must be a core consideration of the objects and principles of the Bill.

An ‘equitable and prosperous city’ object

We recommend the insertion of a coequal ‘equitable and prosperous city’ object as a new paragraph 7(1)(d) of the Bill, to be defined in a new clause 8A in a similar fashion to current clause 8. This new object would add clarity, while ensuring that the social and economic goals that Canberrans expect of the planning system are given sufficient weight.

| Recommendation 1: An ‘equitable and prosperous city’ object should be inserted into the Bill as a coequal object to the ‘ecologically sustainable development’ object. |

Key concepts in this new object should include:

-

Minimising housing costs for Canberrans while ensuring high standards of housing

-

Ensuring that there are housing options for all Canberrans - including public, social and affordable housing - regardless of income

-

Ensuring that every district of Canberra has abundant affordable and social housing to prevent spatial socio-economic segregation

-

Eliminating poverty and unsheltered homelessness

-

Minimising the financial, environmental and temporal costs of transporta, goods and services to Canberrans. The planning system should enable cheap, low emission, easy access to key locations via efficient public transport, mixed land use and walkable neighbourhoods

-

Ensuring abundant provision of cultural, social and civic infrastructure such as libraries, theatres, parks, sporting facilities, and parks

As this object would be read alongside and have equal status with the existing ‘ecologically sustainable development’ object, it would not adversely impact the Bill’s strong emphasis on environmental and ecological protection.

Affordability principles

Housing affordability’s only mention in the principles of good planning is as a subcomponent of ‘activation and liveability principles’. Given the impact that the planning system has on housing affordability, it needs to be elevated to a top-level set of principles.

| Recommendation 2: The ‘activation and liveability principles’ should be split into the separate ‘affordability principles’ and ‘activation and liveability principles’. |

The affordability principles should include:

-

Urban areas should include a range of high-quality housing options with an emphasis on living affordability (from the current activation and liveability principles)

-

Planning and design should strive to reduce housing, transport, food, and other living costs, both financial (as a percentage of median disposable incomes) and temporal (time and convenience)

-

Places - employment, housing, amenities, services, green space, etc - should be located such that they are temporally proximate to each other. Walkable, mixed use localities with efficient and frequent public transport are key to the future of Canberra. An objective of planning should be to minimise the amount of time that people spend in transit a month while getting to where they need to go.

-

Planning, design and development should strive to eliminate poverty and homelessness, particularly through planning’s ability to reduce the financial and temporal cost of necessities (housing, transport, food, education, healthcare). Planning and design can alleviate or exacerbate the deprivation and exclusion of poverty and homelessness.

-

Urban areas should be planned, designed and developed to have an abundance of housing affordable to the least well off in society (by public, social, inexpensive or otherwise affordable housing). Districts should be planned to ensure that this housing is evenly distributed across Canberra, minimising spatial socio-economic segregation.

We draw the Committee’s attention to a number of the other submissions to the Directorate on the exposure draft which similarly recommend the addition of more detailed housing affordability objects and principles, such as those of the Planning Institute of Australia (ACT Division) and the Housing Industry Association.[2]

Fixing merits review

The Bill does not address a serious failing of the existing planning framework, namely the role of merits review in the form of appeals to the ACT Civil and Administrative Tribunal (ACAT).

In its current form, our merits review system is costly, inefficient and unsatisfactory. It fails to meet the needs of the community, of planners and of proponents. Community groups who regularly appeal decisions complain that the system is cumbersome, difficult to engage with (due to the complex, court-like, adversarial nature of ACAT) and a poor replacement for meaningful consultation. Proponents and ACTPLA find the system expensive and risky, without creating clear improvements in planning outcomes.

Most importantly, the current system has a serious chilling effect on development in the ACT, especially with regard to the building of much-needed new social housing and community amenities in existing suburbs with high housing costs.

We also believe that social and public housing developments should be exempt from the merits review process. Decisions surrounding public and social housing determine the quality of life for the most vulnerable of our society and our planning system should reflect the importance of this. Impoverished Canberrans are spending years on waiting lists. Allowing a few, primarily wealthy and established residents to hold up these developments, often on “neighbourhood character” grounds, has real world impacts on Canberra’s worst off citizens. At a minimum, social and public housing developments should be made exempt from ACAT merits review.

In this section, we make a number of proposals for designing a new system of review and oversight to achieve better outcomes and a more responsive and democratic planning system.

These proposals are incomplete and would require further policy development on the part of the Government. We are not wedded to the precise details of the system we outline, however we believe the ideas proposed in this section could form the basis for discussion of a better merits review framework.

Recommendation 3: Public and social housing should be excluded from third-party ACAT merits review. Recommendation 4: ACAT merits review should be replaced with a new, non-adversarial system that is more efficient, accountable and transparent. |

Issues with ACAT merits review

ACAT is undemocratic and opaque

Planning decisions are political decisions. Every plan, strategy and code made by EPSDD influences the development of our city and helps determine the society in which we live. Government planners need to consider this when drafting the zoning maps and development codes in the Territory Plan, and then factor this in when assessing the suitability of each DA. In general, our planning system recognises that these political decisions must ultimately be made by the elected representatives of the ACT, or their accountable delegates.

Unfortunately, we do not take this responsible, democratic approach in cases where approval decisions are appealed by third parties. By instead allowing merits review to fall to ACAT - an unelected, undemocratic body that primarily deals with matters impacting individuals rather than the broader community - we diminish the capacity of our elected representatives to plan our city in line with Canberrans’ wishes. As the ACAT processes are structured as litigation between parties, rather than public decision making, the capacity for ACAT members to facilitate consultation from non-parties (that is, the public) when reviewing a decision is limited. ACAT members also, and cannot take the lessons learned from each DA process with them when updating or varying the Territory Plan. Instead, they make determinations that will affect the future of our city based on the narrow interpretation of the single DA in front of them.

This process further subverts democracy by failing to provide equal access to justice for those with and without means. While the barriers to launching an appeal in ACAT are lower than those that exist in other jurisdictions, it is still the case that it requires a significant amount of time and money in order to appeal planning decisions via ACAT merits review. Given the significance of ACAT merits review processes on planning outcomes under our current planning system, this has the effect of ensuring that working people, younger Canberrans, and those on lower incomes have a smaller voice in planning outcomes than those with the means to launch these appeals.

This inequality is further aggravated by the relative lack of transparency provided by ACAT processes (see Box 1).

Box 1: Lack of transparency in ACAT casesUnder current ACAT policy, members of the public who are not joined as parties to a review application are unable to view the case file until after the matter has been fully heard. While hearings are generally open, it is impossible to make sense of the arguments without access to the documents. Additionally, pre-hearing mediation is conducted completely behind closed doors. This leads to an opaque system, where a self-electing few who have the time and money to engage with ACAT determine planning decisions which will affect the future of our city, while the rest of the community must wait to read the final decision. The minimum we could do would be to improve the transparency of these processes. Amending ACAT’s existing policies to permit greater access to documents, and perhaps to require proactive publication of relevant documents, would allow broader community participation in the planning system. Such policies would also be more consistent with the existing rules for document access applied by the Magistrates and Supreme Courts. |

ACAT often leads to fewer homes, and worse planning outcomes

ACAT can act as a handbrake on the necessary housing construction our city needs to ensure that every citizen can have a home. It can frustrate attempts by EPSDD to accommodate its goals such as housing affordability, sustainability, and varied and diverse housing options to accommodate the ACT’s growing population. They also face the risk that ACAT will misinterpret the planning legislation in a manner not intended by the Assembly or consistent with established practice, as occurred in the YWCA case study and resulted in the need for Technical Amendment 2021-14 to clarify the Territory Plan (see Box 2).

The Government already acknowledges that ACAT appeals act as a handbrake on the development of necessary housing and other infrastructure. The current process exempts town centres such as Belconnen and the City, and other important development areas such as the Kingston Foreshore from ACAT appeals, and permits the Minister to call in certain DAs making the decision unreviewable (the Bill replaces this power with Territory Priority Projects that are similarly exempt). The Bill maintains these exemptions and adds in further exemptions for greenfields development in undefined ‘future urban areas’, yet it leaves our established suburbs under the vice of an undemocratic system.

This creates an uneven and perverse system where major developments, such as apartment towers, can proceed without the risk of ACAT appeals, while sensible medium-density housing that we need to fill the “missing middle” can be held up by a few determined residents. For example, in Griffith, the Griffith Narrabundah Community Association has pursued a campaign of objecting and appealing against multiple medium-density Housing ACT renewal projects simultaneously, citing various technical grounds that are unrelated to their fundamental objection to medium-density social housing in RZ1 areas. These appeals are a significant burden on the resources of both Housing ACT and EPSDD.

All of these issues may well be further magnified by a transition to an outcomes-focussed system, which is inherently more discretionary, and may consequently result in a greater role for the individual, subjective preferences of ACAT members. Determination of what outcomes the planning system seeks to pursue, and if developments are consistent with those outcomes should be decided by a body that is ultimately responsible to the Legislative Assembly. A Chief Planner accountable to the ACT Executive is consistent with this principle, while ACAT is not.

Box 2: Case study - YWCA YHomes AinslieA good example of some of the undesirable consequences of ACAT merits review of planning decisions is the recent Tribunal decision in Allen & Ors v ACTPLA & Ors [2021] ACAT 88. This case involved a DA by YWCA Canberra to build a social housing complex on CFZ land in Ainslie. The intended tenants of this YHomes project were women on modest incomes, including victims of domestic violence. This kind of social housing development is desperately needed to address the housing crisis that is most acute among Canberra’s most vulnerable. However, YWCA had the misfortune of proposing social housing in an affluent suburb, with nearby residents who opposed the development. While the stated reasons for this opposition varied, a common theme was that the plot would be best suited for an early childcare facility or some other similar community amenity, even though no such development had recently been proposed. After a long ACAT case, ACTPLA’s approval of the YWCA DA was reversed. There were many contributing factors to this decision, but one particularly concerning one was the Tribunal’s introduction of a novel interpretation of solar access rules that departed from established precedents. This effectively involved two unelected and unaccountable tribunal members dramatically altering ACT planning law. If their interpretation had been allowed to stand, it would have drastically constrained residential development in inner Canberra, and incentivised removal of tree-coverage in order to avoid being subject to the new heightened solar access requirements. This decision was based not upon a particular reading of the planning laws, but rather upon rather vague beliefs about broader community values. ACTPLA subsequently made a technical amendment to the Territory Plan to overturn this interpretation, which we supported. The YWCA has since submitted a second DA, which was called-in and approved directly by the Planning Minister, likely in order to avoid further litigation. Nonetheless, the ACAT cases alone cost the YWCA approximately $250,000, and delayed construction on this much-needed new social housing by many months. The cost to the taxpayer due to legal representation for ACTPLA is unknown. This case illustrates two key points. First, merits review leads to a convoluted planning system with poor design and planning outcomes. Second, ACAT merits review creates significant inequalities in our planning system by allowing a wealthy few to foist significant legal expenses upon developers - including non-profit organisations relying on government grants and charitable donations - even where these developments have broad community support. Forcing social housing developers to rely on Ministerial intervention in order to build new housing in wealthy suburbs has a chilling effect on social housing development in the ACT that is clearly at odds with the ACT Government’s broader policy goals. |

A better approach to resolving planning disputes

We believe planning disputes could be resolved more equitably and democratically by moving away from ACAT merits review.

Interjurisdictional comparisons

The ACT’s current approach to third-party review is far from the only option available. Other jurisdictions (both within Australia and overseas) take a variety of approaches. Within Australia, Western Australia does not allow for third-party appeals on planning decisions at all, NSW only allows for third party merits review of a decision on a DA for State significant development,[3] while Queensland has a specialist Development Tribunal to which only the applicant can appeal and a specialist Planning and Environment Court where third-party objectors can only appeal “impact assessable” development.[4]

In the United Kingdom, planning decisions can only be appealed by the proponent of a development.[5] In their place, the UK provides the community with the ability to create local plans that set out how they want their district to grow. In New Zealand, community input is focused on the plan-making stage of the process rather than encouraging re-litigation of planning decisions as an avenue for disgruntled residents to vent their frustrations with planning outcomes.

Key values and principles for a better review framework

A merits review system ought to be efficient, transparent and accessible, democratically legitimate, consistent and expert.

Our proposals are based around the following key ideas:

-

Upstream consultation: Consultation should be moved ‘upstream’ of individual planning decisions, so that communities can influence overall planning outcomes and create review-exempt exemplary designs that provide both developers and communities with greater certainty

-

Focus on higher-impact developments: Planning review processes should be reserved for larger and more impactful developments. Lower-impact housing projects should not be tied up in review processes.

-

Expert decision making: Where planning decisions must be reviewed, they should be resolved by a panel of planning and design experts, with processes appropriate for achieving better planning outcomes, rather than lawyers following court-style processes.

We propose that the current ACAT merits review process be replaced with an enhanced reconsideration process, with interested parties able to request reconsideration from the Chief Planner, who would in turn seek advice from an expert planning review panel.

Upstream consultation

Fixing merits review requires addressing community views and concerns as part of plan-making processes that occur well before any particular development is considered. We believe that effective community consultation at an early stage allows greater certainty for both community members and developers, and can be used to reduce reliance on DA-specific merits review processes.

Better District Strategies

The introduction of District Strategies presents an opportunity to give the local community a chance to provide their views on how the Territory’s planning goals should be achieved at a local level. However, to be effective, they should be designed with concrete targets in mind.

In England, residents can create “neighbourhood plans” and “local plans” which are required to contain clear indications about how an area will increase housing supply to meet demand. In most areas, this requires that the plan must enable an increase in housing supply of 5% more than expected population growth - in high growth areas, this is increased to 20%. Independent planning inspectors review all local plan documents to ensure they are consistent with relevant laws and housing supply requirements. This final stage of review involves extensive consultation to ensure that everyone who may have an interest in the plan has had the chance to comment, not just the louder and oft-heard sections of the community.

Concrete, ambitious and legislated targets for housing supply in each district will ensure that residents are fully informed about the role their district plays in achieving overall housing outcomes, but also have the opportunity to shape how their district manages this change.

| Recommendation 5: District Strategies should include mandatory, ambitious housing supply targets, based on realistic population growth estimates, to ensure that Canberra’s housing needs are met. Extensive community engagement should be used to ensure communities can shape how their district achieves these targets in a fully-informed way, and settle expectations well before individual developments are proposed. |

Advancing exemplary design

One factor that is often raised by Canberrans in relation to new development is a desire to ensure that any new homes built meet community expectations with regard to good design and liveability for occupants. Unfortunately, within the ACT’s current planning system, this sentiment is often channelled not into improved design outcomes, but rather into opposition to any new homes via ACAT appeals and other campaigns against new housing. This means fewer homes for Canberrans to live in, and ensures that many older or lower-quality homes remain in a state of disrepair, because of community fears about what might replace them were redevelopment to be permitted.

To overcome this challenge, we propose the creation of a new ‘exemplar designs’ process, whereby architects and developers could have new high quality designs pre-approved by the community and by a panel of design experts, in exchange for these designs receiving a more rapid and streamlined approval process once development reaches DA stage. While we encourage the Government and Assembly to consider in greater detail how such a process could be designed, we envisage it would involve several elements:

-

Designers and architects would propose designs that meet a range of sustainability, liveability, and cost-efficiency criteria to a panel of design experts, such as an expanded National Capital Design Review Panel.

-

Approved designs would simultaneously undergo a pre-designed community consultation process, that draws on resources such as the YourSay Community Panel, to gain wide-ranging community feedback on various elements of the designs.

-

Once approved by the community and design experts, designs could either be used by the initial proponents, or made available for licensing to any developer in the ACT.

-

Developments that make appropriate use of these pre-approved designs would not be subject to merits review, and would be subject to an expedited DA approval process by EPSDD.

A similar process has already been trialled successfully in Victoria as part of the ‘Future Homes’ program. Overseas jurisdictions, such as the City of South Bend, Indiana, have also developed pre-approved plan programs. The Grattan Institute has also supported the expansion of such programs in order to build community support for much-needed new medium-density development.[6]

| Recommendation 6: The Government should develop an exemplar designs process that gives streamlined approvals and review exemptions to projects using pre-approved designs. |

Place all homes on an equal footing

One of the major flaws of ACAT merits review is that it particularly impacts modest, compact, and often more affordable medium-density homes. Most notably, dual occupancies and multi-unit public housing projects proposed in the RZ1 zone are currently subject to ACAT merits review challenges. This is despite the fact that many of these new projects have similar scale and visual impact as single-unit developments such as ‘McMansions’ that are generally not subject to DA approval, and hence are not subject to ACAT merits review. In these cases, the mere fact that the built form contains multiple smaller units means it can be subject to review and delay by a tiny minority opposed to new housing.

Ultimately, merits review should exist to provide residents with recourse to challenge planning decisions where these decisions could plausibly have a significant negative impact upon their neighbourhoods. Evidently, this is not the case with many low-impact medium density developments in Canberra today, including many multi-unit public housing projects in the RZ1 zone. These projects are often only one storey, and have very limited visual impact on the streetscape. Continuing to allow such projects to be held up by (often unsuccessful) merits review cases does not provide better outcomes for the community, but rather biases our low-density suburbs against the housing that we need.

In light of these factors, we strongly recommend that third-party merits review should be removed from low-impact projects, in particular smaller multi-unit developments in the RZ1 zone.

| Recommendation 7: Third-party merits review should not be available for low-impact projects, in particular smaller-scale multi-unit developments in RZ1. |

An enhanced reconsideration system

Planning decisions are political and public decisions that impact the entire community. The purpose of review of planning decisions is to provide a forum to ensure that all planning decisions are made consistent with the planning policy framework. It should not be a forum to challenge broader questions of government policy - that should remain the domain of the Assembly.

ACAT does not satisfy our key criteria for public decision-making:

-

Efficient - ACAT is supposed to provide an efficient and informal venue for dispute resolution, but in reality, even minor disputes over DAs for as few as two dwellings can take months to resolve and involve multiple days of hearings with expert witnesses. While there is a statutory timeframe of 120 days for finalising planning reviews, this timeframe can be breached. Proponents face significant financial risks from months of delay, in addition to legal fees that can run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

-

Transparent and accessible - ACAT’s role in planning review is extremely opaque, especially while matters are ongoing. ACAT is built around an adversarial legal system that is fundamentally best at resolving civil disputes between private parties or reviewing administrative decisions that affect a single individual’s rights. Planning matters, on the other hand, impact the community as a whole. It is difficult for the community to have visibility of ACAT cases while they are ongoing, and impossible to know the outcomes or considerations of mediation as a non-party.

-

Democratically legitimate - ACAT members are not elected, and are not, in practice, accountable to the Government or the Assembly. This places ultimate decision making power too far away from the body that reflects community expectations. ‘Independence’ of decision making from democratically accountable institutions is not a virtue in planning review. Planning decisions are political decisions that impact the community at large, and the community should expect the ability to influence planning decisions via democratic mechanisms.

-

Consistent - ACAT decisions are often inconsistent with established planning practice, as can be seen with the YWCA case study. Planning decisions often involve application of complex criteria with a degree of subjectivity, which are placed in the hands of individual ACAT members who are divorced from the day-to-day practice of ACTPLA’s planners and can interpret planning rules contrary to their intent, requiring either expensive further appeals or rapid change to legislation to reflect the correct planning intent.

-

Expert - ACAT’s court-like structure and broad jurisdiction across a variety of domains results in an institution dominated by lawyers, rather than planners. While some part-time ACAT members have been appointed for their planning or architectural expertise, and tribunals in planning matters are generally constituted by a member from a legal background alongside a member from a planning or architectural background, the court-like structure of ACAT is ill-suited for having effective discussions about planning principles.

A new system is possible which better adheres to these principles. We propose a replacement for the current third-party merits review process with an new system of ‘enhanced reconsideration’, building upon the existing system of decision reconsideration available to proponents. An enhanced reconsideration system could work as follows:

-

Following the making of a reviewable decision, there would be a window for public comments on the decision (similar to the current window for lodging ACAT review applications), if the DA had received negative representations during the notification phase.

-

As previously stated, it is envisioned that review would be reserved for high-impact development, rather than low-impact development such as medium-density housing development.

-

Developments compliant with pre-approved exemplar designs would also not be exposed to review.

-

-

At the end of this period, the Chief Planner (or their delegate) must decide to refer or not refer the decision to a Review Panel, having regard to the matters raised in the comments and any other matters they consider relevant. They may also decide to refuse the DA outright rather than refer it to a panel.

-

The Chief Planner may decide the scope of matters referred to the Review Panel, as not all comments on a decision may be relevant or meritorious.

-

Review Panels would be constituted similarly to Local Planning Panels in NSW. They would consist of a chair (a senior planner within the Territory Planning Authority), one or two independent external experts, and one community member.

-

The Review Panel would then commence public consultation on the scope of matters referred to them, including calling for written submissions, holding in-person meetings, or any other method they consider appropriate.

-

If the Review Panel forms the view that the DA should be amended, they should work with proponents and other stakeholders to a mutually agreeable amended DA, rather than recommending refusal and that a fresh DA be submitted.

-

The Review Panel then must submit a recommendation to the Chief Planner on the decision, within a statutory timeframe. This recommendation, and all submissions to the panel must be published.

-

The Chief Planner must then make a decision on the DA, with regard to the recommendation of the Review Panel, choosing to accept or vary the recommendation of the Review Panel. If the Chief Planner does not make a decision within a statutory timeframe, the recommendation of the Review Panel is taken as automatically adopted.

Decisions made under this system would still be subject to judicial review before the Supreme Court.

This system would perform substantially better on the key metrics identified above:

-

Transparent and accessible - The recommendations of the Review Panel, its consultation processes and other documentation would be made public in real time, rather than the current opacity of the ACAT document system. The Review Panel would have a wider range of options to engage community members in the review process without requiring them to apply to join as a party in an ACAT case.

-

Democratically legitimate - Final decisions would be made by the Chief Planner, with regard to the recommendation of the Review Panel. The Chief Planner is more accountable to the Executive and the Assembly than ACAT members. If the Government loses confidence in the judgement of the Chief Planner, they can remove the Chief Planner.

-

The Chief Planner is not independent of the Government in this model. That is not a bad thing: it is crucial for accountability of decisions, and for creating a mechanism by which ACT citizens can influence high level planning decisions - by engaging with their democratically elected representatives.

-

The role of the community member on the Review Panel also allows for a level of direct, grassroots democracy absent from the current system. One method of their selection could be by application and appointment by the Minister in a similar method to the approach adopted in NSW. Alternatively, community members of review panels could be selected via sortition in a similar way to jury duty. This could be a powerful way to get voices often implicitly excluded from planning decisions included in the discourse, and a way to avoid the current self-selection biases of those who opt in the debate.

-

-

Consistent - All decisions are ultimately made by a single decision maker - the Chief Planner - who has the power to vary or reject Review Panel advice, and has a deep understanding of the breadth of issues impacting the planning system. This will allow consistent application of policy in line with the overall planning strategy.

-

Expert - Review Panels would include external experts and senior planners in ACTPLA who have much deeper specialist planning knowledge than ACAT. The format of panel deliberations would allow a greater degree of community engagement and better consideration of planning issues than ACAT’s adversarial format.

Role and powers of the Chief Planner

The Chief Planner is by far the most powerful actor within the Bill’s decision making framework. They are the maker of most decisions, or at least have the largest amount of influence over what decisions are made. In particular:

-

The Chief Planner has the crucial power to approve, reject or conditionally approve development approvals, including estate approvals, giving them by far the largest influence over the built form of Canberra. This includes the ability to veto Territory Priority Projects declared by the Minister

-

The Chief Planner has absolute and complete control over the Territory Planning Authority, which is legally an extension of their person under subclause 13(3). This gives them complete and direct control over the priorities and focuses of the Authority (subject to certain restraints such as ministerial directions under clause 17)

-

The Chief Planner prepares the Draft Territory Plan, and while the Executive may refuse to approve it, they cannot directly amend it themselves - instead they may request that the Chief Planner make changes. The Legislative Assembly also cannot amend the Territory Plan once passed to them for ratification

-

The Chief Planner is responsible for reviewing the Territory Plan

-

The Chief Planner has the power to make minor amendments to the Territory Plan, and has the effective ability to veto major amendments, including minister-initiated major amendments under paragraph 63(1)(b).

We are not opposed to the planning system having an actor who is empowered to make decisions and resolve the inevitable tensions between competing interests, institutions and policy objectives, as the Chief Planner largely can do. There can be no accountability for decisions in a system where no one is sufficiently responsible for outcomes to be held accountable for them.

A key weakness of our current planning system (and many planning systems globally) is the fragmentation of decision making power between many institutions and statutory officeholders. Quite often these institutions have very narrow mandates (Heritage Council, Conservator of Flora and Fauna) and cannot holistically balance the many other considerations beyond their purview when making decisions that interact with the planning system. A single actor that is capable of making and being accountable for decisions is desirable.

Our view, however, is that this actor should be ultimately democratically accountable to the ACT electorate. Planning decisions are political decisions, and Canberrans should be able to democratically shape our planning system by electing a government that shares their values and priorities.

In the Bill, the Chief Planner is a statutory officer holder that can only be dismissed for cause, meaning they are not accountable to the Minister or to the Assembly. Clause 29(1) establishes the circumstances under which a Chief Planner can be dismissed, mostly for reasons of corrupt, criminal, or other misconduct.

It appears unlikely, under the current drafting of these provisions, that the Assembly or Executive can dismiss the Chief Planner because they have lost confidence in the Chief Planner’s ability to perform the role, either due to underperformance or lack of alignment with the Government’s planning priorities and vision.

This could give rise to a whole collection of unfortunate situations including:

-

The Chief Planner may be appointed for a term of up to five years, which is longer than the four year Legislative Assembly term. It is possible therefore for an outgoing government facing probable electoral defeat to install a partisan Chief Planner with the aim of frustrating the new government’s planning or infrastructure agenda for the entire next term of government.

-

A government may promise to build a key piece of infrastructure (such as light rail, a hospital extension or so on) in an election, and subsequently declare that project a Territory Priority Project, only for the Chief Planner to then veto the project on the basis that they do not believe the project is conceptually consistent with their own interpretation of the principles of good planning.

-

The Minister may initiate a major amendment to the Territory Plan, directing the Chief Planner to prepare a draft amendment under paragraph 17(1)(b). The Chief Planner could then oppose the amendment, and withdraw it under paragraph 63(1)(b), effectively vetoing the major amendment.

-

The Chief Planner may fail to act in a way that is sufficiently aligned with the Statement of Planning Priorities, Planning Strategy or general policy direction from the Minister in exercising their functions, including by deliberately not acting on priorities of the elected government.

We would hope that none of these situations ever occur. However, the Bill at the moment does not have a satisfactory method of resolving them, unless the Chief Planner having a disagreement with the Government or Assembly, on matters of policy and exercise of their functions, qualifies as ‘misbehaviour’ under paragraph 29(1)(a).

We also note that unaccountable decision makers holding strong political views, and using their power over planning decisions to realise those views is unfortunately all too common. For instance, the views of the National Capital Development Commission’s first Chief Planner, Peter Harrison, architect of the Y-Plan here is instructive. During his tenure, Harrison:

-

Described street life as a ‘third world notion’ that was the result of inadequate housing

-

Described walkable suburbs in other cities, like Glebe, as ‘vestiges of the third world’[7]

-

Described public transport as a ‘welfare service’[8]

-

Described terrace housing as a ‘denial of human dignity’ noting that ‘I don’t regard a terrace as fit for human habitation.’[9]

We still live with the consequences of Harrison’s beliefs today.

Planning then, is too important to be left to planners without political oversight and accountability from the elected government.

The appropriate conception of the Chief Planner is as an agent of the Executive that is in turn accountable to the Legislative Assembly. The elected government of the ACT should be able to have a Chief Planner that is aligned with their values, priorities and objectives, and to dismiss Chief Planners that frustrate their democratic mandate.

This would make our planning system more democratically responsive and ensure better alignment between the Minister’s, the Executive’s and the Assembly’s vision for the planning system (reflected in the relevant strategies and plans) and the implementation of that vision through decisions on individual DAs and the Territory Plan.

We are of the view that the risks from this change, such as perceived politicisation of the role or undue political influence over individual DAs are sufficiently mitigated by the practical and political costs of dismissing a Chief Planner, and the high bar of requiring Cabinet approval for such a decision.

| Recommendation 8: The Chief Planner should serve at the pleasure of the ACT Executive, without a fixed term. |

We also note that some other bodies have proposed that the problem of the Chief Planner’s powers and lack of accountability be addressed by creating panels of other unaccountable, unelected statutory officeholders to review their decisions. We are of the view that this would make decision making slower, more expensive, internally inconsistent, and more likely to be influenced by special interests.

Fast-tracking critical infrastructure: Territory Priority Projects

We firmly support giving elected governments the ability to say “yes” to vitally needed development, and believe a fast-track mechanism for high-priority projects is necessary to avoid critical infrastructure projects being stuck in litigation.

The current planning framework achieves this through the use of call-in powers, allowing the Minister to personally make a decision on any DA they deem to be significant, which is excluded from ACAT review. The new framework proposes to remove call-in powers and replace them with a new Territory Priority Projects system, largely in response to concerns from some sectors of the community about the use of Ministerial powers.

The exposure draft version of the TPP provisions had an overly high bar for declaring a project to be a TPP, and also gave decision-making authority over the DA to the Chief Planner rather than the Minister. In our exposure draft submission, we raised concerns about the requirements for declaring a TPP being overly strict and potentially exposing many TPP declarations to judicial review. Other submissions raised concerns that transferring decision-making powers away from the Minister risked removing political accountability for difficult planning decisions. The current version of the Bill addresses these concerns by modifying the requirements for declaring a TPP, and giving the final decision on a TPP DA to the Minister.

We support the revised version of the TPP provisions and believe they are an appropriate way to ensure that critical projects can be fast-tracked while maintaining political accountability through a Minister who is accountable to the Assembly and the electorate.

Public consultation can’t be dominated by the few

Public consultation is a long-standing element of Australian urban planning processes, and high-quality consultation processes are widely recognised as important in ensuring the needs of the community are factored into planning. However, public consultation processes as currently practised are often deeply flawed, resulting in outcomes that do not accurately reflect the needs of the entire community. Consultation processes must not become vehicles for small and unrepresentative groups to put their own interests ahead of those of the broader community and block change that is necessary to achieve positive outcomes for Canberra as a whole.

The Bill introduces the concept of principles of good consultation, which must be considered by decision-makers when undertaking public consultation. While our preference, as expressed in our exposure draft submission, was for the principles to take the form of a disallowable instrument, we support the Bill’s proposed principles of good consultation as a framework for community involvement.

In particular, we strongly support the inclusion of the “balanced” and “inclusive” principles. Public consultation processes often struggle to properly represent the diversity of Canberra’s community, and favour residents from higher socioeconomic and educational backgrounds (who are disproportionately homeowners rather than renters). People who are time-poor, due to work or family commitments, have difficulty making a meaningful contribution - it can be very difficult to attend meetings or write lengthy submissions with hard deadlines. The outcomes of consultations are often biased towards retirees and those without dependents.[10]

Residents’ associations and community councils often play an outsized role, as few people are sufficiently engaged to make substantive submissions on the highly technical issues of planning. However, while they may play an important role in representing certain constituents in their neighbourhood or district, the reality is that their membership bases are often nowhere near as diverse (in a number of ways, including age, socioeconomic status and cultural and linguistic background) as the broader community.

The “balanced” and “inclusive” principles could be further improved by explicitly acknowledging that the needs of potential future residents, not just existing residents, must be considered. This is particularly applicable to District Strategies, where the views of current residents, community councils and residents’ associations need to be considered in the context of the needs of the broader Canberra community. We acknowledge that planners already do attempt to factor in the needs of future residents as a public interest consideration in their decision-making processes, however, while not always practical, where possible, consultation efforts should find ways to engage potential future residents and community organisations that are not tied to a particular geographical area.

| Recommendation 9: The principles of good consultation should explicitly acknowledge that public consultation processes should, where possible, include the needs of potential future residents and the broader Canberra community. |

We strongly believe that consultation must be a mechanism to utilise local knowledge, improve planning outcomes and satisfy competing planning needs, rather than an opportunity for a small subset of the community to veto change at the expense of others. Public consultation outcomes that are unrepresentative of the Canberra community should not be given undue prominence in decision making. Public consultation needs to capture the views of the broader community, not just the loudest voices who happen to turn up.

While the principles of good consultation lay out an overall framework for what consultation should look like, the actual effectiveness of this framework will depend on the practices recommended by the good consultation guidelines (clause 12). We are specifically concerned with developing practices that will successfully implement the “balanced” and “inclusive” principles.

Representative population samples, obtained using statistically-valid techniques, should be used wherever possible to capture the needs of different demographic groups (such as age, gender, income, education, cultural background, and homeownership status). This is particularly important for consultations with a broader impact, such as the Planning Strategy and District Strategies.

Consultation processes must have appropriate avenues for low-cost forms of engagement that do not involve attending meetings or making lengthy submissions. This could be done in a variety of ways, and the guidelines should encourage innovative approaches. Such participation should be treated as equally as possible with higher-cost forms of participation, however the focus should never be on the mere quantity of submissions.

| Recommendation 10: The good consultation guidelines should include best practices such as representative population sampling and low-cost forms of engagement (where appropriate, given time and cost constraints) in order to successfully implement the “balanced” and “inclusive” principles. |

Improving the other principles of good planning

Activation and liveability principles

Currently, the activation and liveability principles are the most substantial of the principles of good planning, containing the largest number of subcomponents, and covering a broad range of issues - including integration of public transport and active travel, mixed land uses, housing mix and affordability, and amenity.

As stated in Recommendation 2, we specifically recommend that the affordability-related element of the activation and liveability principles should be separated into a separate set of principles.

The remaining activation and liveability principles should place further emphasis on proximity, public and active transport, and explicitly state the importance of civic infrastructure.

Recommendation 11: The activation and liveability principles should be amended to:

|

High quality design principles

We agree with the vast majority of the high quality design principles, especially in relation to built form accessibility and inclusivity, contribution to the urban forest, and the connection of places with each other.

We have concerns with two elements of this principle:

-

Paragraph (a) appears to be a major barrier to the evolution of localities to meet our city’s changing population and needs

-

There appears to be no element of this principle ensuring that the actual built form is high quality in a practical sense (energy efficiency, safety, high quality construction, etc), rather than abstract concepts of aesthetics.

Paragraph (a) of the high quality design principles currently provides that:

(a) development should be focussed on people and designed to—(i) reflect local setting and context; and

(ii) have a distinctive identity that responds to the existing character of its locality; and

(iii) effectively integrate built form, infrastructure and public spaces;

Again, the Territory Plan must ‘promote’ principles of good planning. This creates an obvious difficulty, because if the Territory Plan must promote development that ‘reflects local setting and context’, then how can the Territory Plan ever decide that the local setting and context should change?

Over time, the character and context of localities will and must change to meet the needs of a growing city and changing economy. Kingston Foreshore, the Lonsdale/Mort Street area of Braddon, NewActon, and vast stretches of the Woden and Belconnen town centres are all examples of positive change in our city, which have received significant community support.

The ability of the Territory Plan to change intended land use to meet the coming challenges of creating a more affordable, liveable, sustainable, compact and efficient city should not be hampered by this tautology within the high quality design principles.

Recommendation 12: The high quality design principles should be amended to make explicit that local settings and contexts can evolve over time, including through development, to better meet changing community and environmental needs. Recommendation 13: The high quality design principles should be amended to include a provision related to building quality and energy efficiency. |

Investment facilitation principles

Economic considerations should be core to the planning system. A prosperous city with low costs of living, high wages, and a diversified high-skill economy is crucial to increasing quality of life, minimising poverty, and ensuring that our city has the tax base needed to address the climate crisis and other public policy challenges, while providing the services (education, healthcare, social security) and infrastructure that residents expect.

The investment facilitation principles express these considerations well, but we believe the phrase ‘investment facilitation’ does not properly reflect the impact these issues have on the lives of all Canberrans, not just businesses and investors.

Additionally, these principles should be further strengthened:

-

Planning and design should aim to maximise the discretionary (after tax, housing and other necessity costs) income of residents at every income level

-

Planning and design should aim to minimise poverty within our city, in a way that is consistent with and mutually supports the poverty alleviation element of our proposed affordability principle.

| Recommendation 14: The investment facilitation principles should be renamed ‘economic prosperity principles’ to better reflect their nature and aim, and should express a goal of maximising incomes and minimising poverty. |

Cultural heritage conservation principles

The introduced version of the Bill introduces a new set of ‘cultural heritage conservation principles’ that were not included in the exposure draft of the Bill. We recognise that heritage should be a consideration in the planning system, in common with and balanced against other factors and considerations.

However, the prevailing interpretation of ‘heritage conservation’ in Australia means that heritage conservation frequently exists in tension with the other objectives and principles of good planning. Excessive heritage conservation constrains housing creation in well-located areas, which in turn drives environmental and ecological destruction from increased greenfield suburban sprawl.

The fact that ‘cultural heritage conservation principles’ are a standalone principle of good planning, while housing affordability is not, is a major concern. Where housing creation clashes with strict interpretations of heritage conservation, the correct statutory interpretation would currently appear to be that heritage is a superior consideration to housing affordability as a result. This is undesirable, and affordability should be elevated as a full principle to prevent this.

Additionally, there are a number of other issues with the drafting of the principles in the current version of the Bill.

Paragraph (b)(i) provides that ‘development should respect local heritage’, however:

-

‘Local heritage’ in the ACT does not clearly and unambiguously simply mean ‘heritage that is nearby’. The ACT Heritage Council Heritage Assessment Policy identifies ‘local heritage’ as a lower level of heritage significance beneath the threshold for heritage registration by the Council. It is not clear from the current drafting if the paragraph is intended to mean ‘nearby heritage meeting the local heritage significance’ or ‘nearby heritage meeting the Territory heritage significance threshold required for heritage registration under the Heritage Act 2004’. This ambiguity should be resolved.

-

Setting the threshold for engagement of this principle at the local heritage significance level would be undesirable. This would create separate thresholds of engagement for the Heritage Act 2004 and consideration of heritage under this principle. This would create additional complexity in the system and increased ambiguity, as many places may have “local heritage significance” that are not registered by the Heritage Council and cannot be identified ahead of time.

-

It is not clear what “respects” means in this context, and what this practically means as a principle of good planning.

Paragraph (b)(ii) provides that development should ‘avoid direct impacts on heritage or, if a direct impact is unavoidable, ensure that the impact is justifiable and proportionate.’ This raises the following issues:

-

“Heritage” is not defined in the Act, and it is not clear what degree of heritage significance engages this principle to avoid direct impact.

-

It is not clear what “justifiable and proportionate” impact is. This language appears to imply that a development can minimise heritage impact on adjacent heritage values simply by reducing its scale. This is misplaced and one of the major drivers for how concepts of heritage conservation limit housing creation and density. Heritage values are not inherently damaged by larger scale new developments, and the Act should not assume that this is so.

Recommendation 15: References to “heritage” in the cultural heritage conservation principles should be amended to refer to heritage places and objects that have been registered under the Heritage Act 2004, to provide certainty as to what places and objects engage this principle. Recommendation 16: The language of the cultural heritage conservation principles should be reworded to provide that the focus of the principle is to conserve the heritage value of existing heritage places not to constrain nearby development in a way that dampens the potential for architectural expression and the creation of additional housing and services. In particular, references to “proportionality” should be removed to avoid the implication that adjacent developments should be scaled down near to heritage places. |

[1] “Affordability should be front and centre of planning reforms”, 16 March 2022, https://www.greatercanberra.org/blog/media-release-affordability-should-be-front-and-centre-of-planning-reforms/

[2] Planning Institute of Australia (ACT Division), PIA ACT Submission - Draft Planning Bill, 15 June 2022; Housing Industry Association, Submission to ACT Planning System Review and Reform Project 2022, 15 June 2022

[3] Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 No 203 (NSW) Div 8.3

[4] Planning Act 2016 (Qld) Schedule 1; Environmental Defenders Office (Queensland), “Appealing, Enforcing Development Approvals and Seeking Declarations”, December 2017

[5] Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (UK), section 78

[6] Designing Better Suburbs, Brendan Coates, 5 November 2022.

[7] National Library of Australia, Interview with Peter Harrison by James Weirick, 1990, session 1, 00:17:

[8] National Library of Australia (Trove), Peter Harrison ‘The Disaster of Civic’ Letter to the Editor, Canberra Times, 2 October 1986

[9] National Library of Australia, Interview of Peter Harrison by James Weirick, 1990, Session 3, 00:11:05.

[10] See, for example: Einstein et al., Still Muted: The Limited Participatory Democracy of Public Zoom Meetings, 2021; Taylor, Elizabeth & Cook, Nicole & Hurley, Joe. (2016). Do objections count? Estimating the influence of residents on housing development assessment in Melbourne. Urban Policy and Research. 34. 1-15. 10.1080/08111146.2015.1081845.